|

Subscribe to Searchlight Magazine

In Search of Refuge

by Kate Taylor

Kate Taylor interviews Ladislav Balaz, a Rom

refugee who formed 'Europe Roma' in order to help others who have fled

to Britain from some of the most appalling prejudice in Eastern Europe

Ladislav Balaz sits in his small office in north London, speaking

Romani with a family who seek help from him. He is well placed to

understand the problems they face in Britain, and he also possesses a

unique insight into the situation from which they have fled. For

Ladislav is himself a Rom refugee, forced to leave his home in the Czech

Republic due to the rising tide of racism being perpetrated against the

Romani people.

Unfortunately such prejudice has gained momentum in the years following

the collapse of the Eastern bloc. Arriving in Britain three years ago,

Ladislav encountered first hand the asylum process that has so far

refused to grant any Roma asylum status in this country.

It was against this backdrop that Ladislav formed Europe-Roma, an

organisation that seeks to give Romani asylum-seekers in Britain proper

legal representation, advice, accommodation and simple day-to-day

possessions that are so lacking. Ladislav works primarily with Roma from

Slovakia, Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Russia and other eastern

European countries, "but I help all refugees", he adds. On arrival in

this country, more often than not, Roma are faced with desperate poverty

and expressions of racism. Yet they find themselves vilified by the

British media and politicians for trying to provide for their families.

The view perpetrated is that the Roma are solely economic migrants who

have no right to asylum in Britain.

But the situations from which they are fleeing stand in stark contrast

to this perception. In the Czech Republic, Ladislav encountered on a

daily basis the anti-Roma bias that has become entrenched in the

country: "every day they attack Roma ... skinheads and fascists march

and fight on the street ... I was in the same situation with my family -

it was horrible. But nobody would help us, nobody. And all the people

agree with the skinheads, it is like many years before, during Hitler."

In frank and moving terms, Ladislav relates the circumstances

surrounding the anti-Roma wall erected in Usti nad Labem, and also talks

of an attempted pogrom on Roma in a restaurant in the town of Ceské

Budejovice last year. Skinheads entered the building shouting "Sieg

Heil", "Gypsies to the gas chambers", and other racist slogans. Armed

with stones, bottles and even guns, the skinheads relentlessly attacked

the 40 Roma inside the restaurant. These are just two examples of the

racism that permeates Czech society and is directed towards the Roma. In

many instances the police and courts turn a blind eye and many

mainstream politicians espouse racist sentiments in public, effectively

sanctioning the actions that can ensue from such attitudes.

Ladislav believes that the treatment of the Roma is a litmus test for

any humane society. It is for this reason that he believes the Czech

Republic should not be allowed to join the EU. His quest to alert people

to the situation of the Roma in eastern Europe has taken him down many

avenues, even to the House of Commons, where last year he addressed

Parliament. Ladislav has a simple question: "I want to know why this

government gives support to the racist Czech Republic ... that is why

the Roma have to come here ... I've met Barbara Roche, Jack Straw,

Jeremy Corbyn, Dianne Abbott ... We are talking to everybody about the

situation in the Czech Republic. There it is a very hard life, you

know."

For those that do make it here against the odds, the ordeal is not

over. When they arrive they are accorded little in the way of help or

dignity as human beings. Ladislav estimates that around 6,000 Roma

refugees from eastern Europe in Britain, out of a world population of

around 10 million. Often Roma are dispersed widely across the country,

allowing them to have little contact with others in their situation, nor

to build up any sort of community. "These people are sent everywhere, to

Coventry, Colchester, Liverpool, Leeds, Birmingham, and so on. But I am

starting to drive everywhere to visit these people, to try and help

them."

Ladislav also mentions cases where families have been deliberately

separated from one another. One Roma refugee was sent to Manchester and

when his wife arrived in the country later, she was sent to Colchester.

"When this action was questioned, they were told, 'if you won't stay

there, we will give you your passport back and you can leave'." Ladislav

took this case to Refugee Action and the family now lives together. But

this case is just symptomatic of a wider attitude towards refugees that

is both endemic and unchallenged.

"Many people just do not understand what a refugee is. They just

understand what they hear and think these people are just after money,

that this is merely an economic problem, that they steal and so on. But

this is just not true."

Ladislav is a man whose own experiences are interwoven into his work

and his quest for justice for Roma refugees. It is not difficult to see

why he speaks so passionately about his desire for a better life for the

Roma. But the problems did not end for Ladislav after he arrived in this

country: he has struggled to gain refugee status, money is vastly

lacking, he lives in a five-bedroom house with 35 other people and he

has been attacked four times by racists. Throughout this period, life

was terrifying for Ladislav and his family and they would stay up all

night for fear of further assaults. He was told he could not be moved to

new accommodation because he only had temporary permission to stay in

Britain. But this has given him greater insight into the work that needs

to be undertaken in order to change things, no matter how small the

steps might have to be.

Sometimes it is the little things that bring hope to those in desperate

situations. At Christmas, Ladislav cooks for other Roma families and

collects clothes and toys for the children. But good intentions do not

always map out when one is faced with the bureaucracy and obstacles of

the asylum process. When Ladislav tried to deliver items to Oakington

detention centre on Christmas Day, an officer told him that they could

not take any of the presents. "I said look, this is detention not

prison, why do you do this? And he replied, this is policy."

It is stories such as this that have prompted Ladislav to change the

name of his organisation from Europe-Roma to the West European Roma

Rights Centre. This, he says, is to ensure that civil rights abuses

against the Roma in this country do not continue unchecked. "I want to

monitor this government, these police, these court cases and how they

deal with the Roma. Because many police, immigration officers, detention

centres and prisons break the law. When we find out which people are

bad, we will write reports about this and get more witnesses to speak

about the situation in the UK. We will hold people accountable. This is

my future in the organisation."

In Ladislav's opinion the Roma have every right to seek refuge in

Britain. "We are from a former English colony. At the moment, we, the

Roma, are not on the map. But we came into Europe from north India 1,000

years before. Now we don't have a country, everybody, everywhere is

fighting the Roma ... If this government accepts people from India, they

must accept the Roma. I have lots of friends from India and we have the

same language.

"Last month I spoke at a Fire Brigades Union conference. Many people

there asked me, 'Ladislav, do you have a country?' and I said no. They

again asked me, 'Ladislav, where are you from?' and I said the Czech

Republic. They say, 'then this is your country'and I say no, I was just

born there. But my parents and grandfather came into Europe from north

India, this is my country. And they all agreed and said Ladislav, you

must tell this situation to this government. They must learn this. I

said look, this government just likes to talk about money, and all they

are talking about is petrol and fuel and the weather, not about people.

This is very bad. It is the same in the Czech Republic. This is a bad

situation."

Despite Ladislav's dedication to his work, the strain on him personally

has begun to take its toll. The organisation receives no funding and

relies on small donations and help from individuals. The constant

travelling and frustration that accompany the job offer few rewards.

"It is no life for me ... I come home and everybody is asleep. I don't

see my children. You know, this is very hard. I am so tired all the

time, it never stops." But in spite of the effect on his personal life,

Ladislav remains determined to create a more positive environment for

Roma refugees in Britain.

"I visited the Refugee Council and I talked to them. I asked them what

they are doing, how they are dealing with the situation and they said to

me look, this is our job, not yours, go. This is very bad. I think that

if all the organisations in the UK go in together and fight bad

policies, it would be much better."

This is the vision that Ladislav holds for the future. The barbaric

racism that he encountered in the Czech Republic, alongside the inhumane

asylum process that he has faced personally in Britain, have led to a

desire to channel these experiences into something positive for others

who are overlooked and marginalised by society: "I want to be a man who

has power over Roma rights, this is my future. If we get no help, I will

do it myself."

Searchlight November 2002

The secret that lurks deep in the US far right

The Terrorist Next Door: The Militia Movement and the Radical Right By

Daniel Levitas

Thomas Dunne Books, St Martin's Press.507 pages, plus photographs.

$26.95

Reviewed by Leonard Zeskind

Despite an insidious invasion by McDonald's hamburger stands and the

omnipresence of Cable Network News, Europeans must find the political

culture of the United States baffling. Even access to the worldwide web

cannot adequately explain the fervid attachment to guns and religion

that shapes our national identity. Here myriad "Christian" movements

grip civil society more surely than Queen Elizabeth's crown fits her

head. Here the National Rifle Association can swing a Democratic

majority over into the Republican column. Where in Europe have "gun

rights" activists cast the deciding votes in an election? And where can

Brits and other Europeans learn the history and politics of that most

quintessential Americanist of white-wing movements: the Posse Comitatus

and its Christian patriot and militia descendants? Fortunately, Dan

Levitas has provided the answer in

The Terrorist Next Door: The Militia Movement and the Radical Right.

When asked to explain what the term "Posse Comitatus" means,

journalists usually begin by translating the words into the phrase "the

power of the county". They then discuss a drive for local control. How

else to understand a movement that opposes the current established

political and social order, yet stands in the oldest of American

traditions? That wraps itself in the red, white and blue, yet is revered

by the brownshirt and swastika armband. That is militant, even violent,

but attracts average white people as if it was a Rotary Club or

Brotherhood of Elks.

Well, Levitas successfully demonstrates that the Posse Comitatus is all

of the above, yet much more. He shows how it was founded on the

unequivocally racist and antisemitic theology of Christian Identity: the

belief that Jews are satanic, and that black people and other peoples of

colour are less fully human. That the Posse holds laws enacted by local,

state and federal legislatures as secondary to what they call "Christian

common law". That a fundamental divide separates the citizenship rights

of white Christians and those of all others. And he tells the story of

how this organisation and this ideology animated three decades of

far-right activity. First in the tax protest movement of the 1970s, then

in the farm crisis of the 1980s, and finally in the militia movement of

the 1990s, the Posse Comitatus phenomenon swelled with new recruits

drawn from the mainsprings of middle American life.

Levitas first encountered the Posse and other white supremacists two

decades ago, while working for a group called Prairiefire Rural Action

in Iowa. At that time he carried two portfolios. One was as an advocate

for family farmers facing economic and social dislocation. With the

second he fought off the hate-mongers blowing across the prairie like an

ill wind. Over the next years he became a preeminent student of racist

and antisemitic organisations and a leading activist in the movement to

oppose them. He wrote widely, including an encyclopedia entry on

antisemitism and as an editor and contributor to the 1992 volume,

When Hate Groups Come To Town. He has testified repeatedly as an

expert witness on hate groups for state and federal courts in the United

States, as well as for Canadian courts. With unmatched investigative

zeal and a multi-layered knowledge of his subject, Levitas has now

written the most comprehensive and (accurate) book on the Posse

Comitatus, the militia movement and the rural radical right.

The Terrorist Next Door weaves the broad tapestry Europeans need

to understand the particularities of this very American topic. It also

serves as a corrective to many of the mistaken notions that have plagued

other accounts. And it will fascinate the average non-specialist reader.

If it sounds like I'm a Levitas fan, I am. He and I have worked closely

together for 20 years, including years as friends of Searchlight

in the United States. But any objective critic will have to acknowledge

that he has told here a groundbreaking story.

Levitas traces the origins of the sheriff's posse back to jurisprudence

in 13th century England. He also nails the original Posse Comitatus Act,

passed in 1878, to the return of Southern-style white supremacy after

the Civil War. He shows how that law was designed to prevent Union

troops from protecting the rights and lives of newly freed slaves in the

post-Civil War South. Using a few main characters as his narrative

needle, he successfully threads the reader through the right wing in the

1950s and 1960s, when the battle to preserve Jim Crow segregation was

fought on an ever-shifting Cold War terrain. One moment McCarthyism

bolstered antisemitic conspiracy myths and decimated the communist and

socialist movements. In the next, President Eisenhower called in federal

troops and ensured the desegregation of schools in Little Rock,

Arkansas. By plumbing these depths, Levitas's history challenges some of

the received wisdom by which that period is understood.

Most importantly, Levitas finally corrects the record on the origins of

the contemporary Posse Comitatus. For almost 30 years, the FBI and

others have described one Mike Beach of Portland, Oregon as the Posse's

founder. Not so, Levitas writes. And he has the documentary evidence to

show that the founder was actually Bill Gale, and that Beach copied

Gale's propaganda and claimed it as his own. Gale is the central

defining character in this book. It was Gale who grafted the tax protest

movement onto the trunk of Christian Identity theology.

It was also Gale's ideas and personality that tortured the situation in

the rural Midwest. Family farmers, organised by the American Agriculture

Movement, rode tractors to Washington DC, staged courthouse protests and

fought both Presidents Carter and Reagan on federal agricultural policy.

The Posse Comitatus and other white supremacists sensed in this conflict

a harvest of new recruits. And they spread across the countryside like a

herd of locusts. For a while, the Posse turned the battle over the price

farmers received for their corn harvest into a blind alley fight against

the mythical "international Jewish banking conspiracy", instead of one

targeting multinational grain traders and politicians who benefited from

their largesse. Progressive farmers' organisations, faced with this

problem of antisemitism eating away at their own ranks, were divided

over solutions. Most wanted to ignore the problem at first. A few tried

to link the fight against antisemitism to a more general campaign under

the aegis of presidential candidate Jesse Jackson. The most effective

response, however, turned out to be confronting the problem directly.

Utilising his one-time position inside the farmers' advocacy movement,

Levitas skilfully parses these dilemmas.

In stark and intimate detail, Levitas also shows a parallel controversy

in the Jewish community. The Anti-Defamation League (ADL), the one

Jewish institution that presumed to be standing guard, was actually

asleep at its post. Virtually blinded by its own ideological

neo-conservatism, the ADL refused to take even its own polling data

seriously. As a result, alternative solutions grew up, outside already

established channels. And these solutions may yet be relevant in other

venues, beyond the American Midwest, where antisemitism raises its head

and draws a mass following.

Levitas continues his history through the 1990s, with the first

emergence of the militias and the bombing in Oklahoma City. By this

reckoning, the militia was the most recent mass incarnation of the Posse

Comitatus. And he demonstrates conclusively that it is impossible

completely to understand the former without a firm knowledge of the

latter. For Europeans unversed in the particularities of the American

far right, Levitas fully connects the Posse and the militia.

Understanding that connection should answer any lingering questions

about armed paramilitaries marching under the banner of Constitutional

fundamentalism. The footprint they leave is assuredly white; and not

some mottled "anti-government" or "populist" colour.

The story that will spin the reader like a top, however, is the

personal biography of William Potter Gale, who was an avowed and

ideological antisemite. To Gale, Jews ran the world in a nasty

conspiracy to destroy "white" civilisation just as surely as the sun

rose in the East. Jews were, to use Gale's oft-repeated slur, "Satan's

Spawn". His was an old sentiment, of course, reflected in Christian

discourse from the "Gospel of John" through Martin Luther and the

Protestant Reformation down to pre-Vatican Two Catholic theology. In

this case, however, Levitas proves that Gale himself was one of the

spawn. That's right. William Potter Gale, who asked the question "how do

you get a Jew out of the tree", and answered it "cut the rope", was

himself born of Russian Jewish immigrants. In fact, all of Gale's

paternal ancestors were devout Jews. Before Levitas, no one had

discovered this hidden story. And you will read about it in full detail

for the first time in The Terrorist Next Door.

This book pulls the reader through 350 pages of history with the ease

and grace of a good story, well told. An additional 35-page chronology

starts with the 13th century legal origins of the concept of a posse

comitatus as found in medieval British law and ends with the terror

bombings of 11 September 2001. Three appendices help flesh out matters

and pictures from the Gale family photo album add to the drama. Add over

100 pages of source-drenched endnotes, and finally a scholarly and

accessible text has arrived to tell this most American of stories to the

whole world.

This book will be available from Searchlight soon or via

www.amazon.co.uk

Copyright © 2002, Searchlight

Book Review

Shared Sorrows by Toby Sonneman

University of Hertfordshire Press Review by Kate Taylor

LAST MONTH, "the campaign group Liberty, acting for the European Roma

Rights Centre and six Czech Roma, entered a British courtroom in a bid

to highlight the depth of anti-Roma bias that pervades the British

government. Human rights activists wanted to declare that pre-clearance

checks, which stopped mainly Czech Roma boarding planes from Prague

airport, contravened the 1951 Geneva Convention, which allows those who

are persecuted in their country of origin to apply for asylum in a safe

country.

But Mr Justice Barton ruled the screening by UK immigration officers,

which has been in place since July 2001, legal. The Geneva Convention,

he said, did not prevent David Blunkett, the Home Secretary, "from

taking steps to prevent a potential refugee from approaching [the UK]

border in order to be in a position to claim asylum, or [making it] more

difficult for them to do so".

That so many Roma not only are refused asylum upon reaching these

shores, but are also prevented from leaving a country where they are

routinely assaulted and even killed, shows a stark refusal on the past

of Western governments to admit that Roma are subject to a catalogue of

human rights abuses.

It is not just in the present day that racism against the Roma is

rendered invisible. During the Nazi Holocaust, the Roma were the only

other group, alongside the Jews, to be singled out for complete

extermination. Yet until recently, the Roma have had little public

acknowledgement of their tragedy.

A number of works have sought to correct this imbalance in the past

decade. Until now, however, most have been from the perspective of

academic distance. Published last month. Shared Sorrows, by Toby

Sonneman adopts an altogether different angle. For Sonneman, "real

recognition is dependent upon caring". And that means abandoning

scholarly detachment in the name of taking us close to the real

suffering of real people.

The intention of Shared Sorrows is to tell a very human story

about a family of Gypsies who escaped the fate that befell so many

others during Nazi rule. It is the author's biographical detail that

renders the book so compelling. On the morning after Knstallnacht, Toby

Sonneman's Jewish father walked through broken glass to apply for the

visa that would save his life. In examining her own family history, the

author discovered the similarities between the fates of the Jews and the

Gypsies in the Holocaust.

Sonnernan travelled with an American Gypsy survivor to Munich, where

she stayed with Rosa Mettbach, another Gypsy survivor. Through Rosa's

story, Shared Sorrows tells the story of a Gypsy family against

the backdrop of Sonneman's own Jewish family.

Rosa identified herself as Sinti. The Sinti are a sub-group of the

ethnic Gypsy population who settled in northern Europe in the eariy

1400s. Bom in Austria, but living in Germany, Rosa lost her entire

family during the Holocaust. Her arm bears the permanent memory of her

time in Auschwitz - the number seared into her skin by the Nazis is

preceded by the letter Z for Zigeuner, the German word for Gypsy,

which is derived from a Greek root meaning "untouchable" and a German

word for "vagrant".

For the author, the sight of the tattoo brings back painful memories:

"When did I first learn to connect images of unspeakable horror and

humiliation with these brands forged on human skin? When did someone -

my mother? - first explain the name? Behind a closed door, in a whisper

chocked by regret: 'Auschwitz'.

"There. There in Auschwitz and in Chelmno, there in Belzec and in

Treblinka, there in Sobibor and in Majdanek, there were other sorts of

ovens, ovens that produced not sweet pastries but only bitter ashes. In

the Gypsy language, Romanes, there is a saying: 'Our ashes were

mingled in the ovens'. There had our peoples been inextricably bound."

This is the message that Rosa's story gives us. The shared sorrows of

two people have produced a bond that has and will survive the course of

history. It is a history eked with ethnic persecution, racism and

genocide. But it is also a history that has much to celebrate. Both

peoples have shown strength and courage in the face of unspeakable

horrors and this has made their identities all the stronger.

In November 1941, Rosa's family was deported to the Lodz ghetto, but

Rosa managed to escape. She was later captured and sent to Lackenbach.

Rosa escaped again, but her family were not so lucky. They were among

the 5,000 Austrian Gypsies deported from Lodz and killed at Chelmno.

Rosa was later arrested and sent to Auschwitz. Her tenacity yet again

showed its face when she escaped from a labour camp in eastern Germany.

She was sent to jail and was then returned to the labour camp where she

was tortured and put in a dark and narrow cement bunker for four weeks.

But through it all, Rosa survived. And that is what Shared Sorrows

is about: the survival of a people against the odds, both Jews and Roma.

It is the lessons from the past that need to be applied if they are not

to be repeated. The situation for many Roma in both eastern and western

Europe is intolerable. That they are not granted the refuge

to which all of humanity is entitled |i highlights our failure to learn

from the black spots in history. It is that history that Toby Sonneman

seeks to keep alive. In doing so, she has done a great service to those

who wish to keep the flames of collective memory burning. But as

Sonneman herself notes, "Conscience is formed by memory, and

these two strands must twist together into one. For memory is essential

- but memory alone is not enough."

Shared Sorrows is essential reading for those who wish to

understand better the tragedy that befell the Roma in the Holocaust. The

power of the book comes from its focus on personal testimonies. It is

through these individual stories of struggle and courage that we begin

to see past the statistics and grant a voice to those who cannot speak.

Searchlight November 2002 11

GERMANY

Fascists routed at the polls

and on the streets

From Tammy Wild in Berlin

GERMANY'S FAR RIGHT took a battering in September's elections to the

federal parliament, the Bundestag. The hard-fought duel between the

Social Democrat-Greens coalition, led by the incumbent Chancellor

Gerhard Schroder, and the conservative CDU-CSU bloc, led by the

right-wing Bavarian Prime Minister Edmund Stoiber, culminated in the

reelection of the coalition but with a reduced majority.

Commentators were unanimous that the return of Schroder as Chancellor

was primarily a negative vote against Stoiber, whose policies included

support for US plans to wage war on Iraq and attacks on the social

welfare system.

For the fascists the results were catastrophic. They failed to make the

leap over the 5% barrier needed to win seats in parliament. But while

the decline of the Republican Party continued everywhere, the party

barely reaching 2% even in its former strongholds in the southern states

of Baden-Wiirttemberg and Bavaria, the nazi German National Democratic

Party (NPD) was able to celebrate some slight local gains in eastern

Germany.

In Brandenburg, the NPD managed an average of 1.5% of the vote - its

highest score nationally - and in Saxony it scored 1.4%. In some small

villages in Saxony, however, between 7% and 10% of voters supported the

NPD, which shows how deeply entrenched the party is in a few areas.

Altogether 214,000 people voted for the NPD nationally but this was not

enough to make the party eligible for cash refunds from the state for

its campaign.

The fascist profile was altogether lower than in the national elections

four years ago. The German People's Union did not contest the elections,

the Republican campaign looked jaded and the NPD ran into anti-fascist

opposition, its events being generally poorly attended.

A new right-wing force, the Law and Order Party (PRO), led by the law

and order crazed judge Ronald Schill, was also wiped out as far-right

voters plumped for Stoiber. Even in its Hamburg stronghold, where last

year it polled 19.4%, the PRO was only able to win 4% and nationally it

took a mere 0.8%.

Aware that it stood no electoral chance and still fearful of being

banned, the NPD has been trying to maintain the frantic pace of activity

it has established since soaking up so many activists from banned nazi

grouplets.

On 14 September, an NPD demonstration in the southern city of Freiburg

im Breisgau turned into farce when, confronted by 15,000 anti-fascists,

the 108 nazis were given an area of 30m by 70m in which to march

silently in front of the station. In a further humiliation, the police

ordered them to remove their boots and march in their socks, to the

great hilarity of the antifascists who had been mobilised by the DGB

trade union federation.

The day turned into a massive celebration by antifascists who held a

rally and listened to speeches and rock music which boomed out from two

huge stages. The anti-fascist demonstration and rally, under the slogan

"Freiburg stands up", was backed by a broad . alliance of trade unions,

political parties, anti-fascist groups, youth organisations, churches

and local businesses, including the city's major department stores.

The NPD's next big outing should have been a march in Munich on 12

October against the Crimes of the Wehrmacht exhibition. Last time the

exhibition was there, in February 1997, the nazis mobilised almost 6,000

people and were supported by right-wing Bavarian conservatives. This

time, they could only muster 300 and were unable to complete their march

through the city centre after 3,000 anti-fascists rallied outside the

DGB's headquarters and blocked their path. The police prevented the

nazis from wearing their usual "bomber jacket and boots" uniforms,

banned them from chanting extremist slogans and arrested 20 of them. It

was another humiliation.

In the NPD's current plight, all that it needed was Nick Griffin,

leader of the British National Party, turning up with his begging bowl.

Griffin recently attended the "Pressefest" of the NPD's rag Deutsche

Stimme, where he was a co-speaker with a horde of convicted nazis

who used to belong to violent fascist organisations that are now

illegal. He also featured as a main speaker at the NPD's "summer

university" in Saarbriicken, where he held forth about the

"achievements" of the BNP.

It is ironic that, after publicly claiming that the BNP Chancellor

needs to move away from Hitlerites, he has opted to Gerhard surround

himself with and be applauded by hundreds of Schroder them, all

belonging to a party the German authorities celebrates want to ban on

the grounds of its nazism. victory

Searchlight November 2002 27

RUSSIA

Russian naasgive the

traditional fascist salute

From Mara Vladimirova in Moscow

Registration of antisemitic party provokes controversy

A NEW RADICAL NATIONALIST PARTY with an openly antisemitic leadership

has received official recognition in Russia. The National Power Party of

Russia (NDPR), which the Russian Justice Ministry registered on 16

September, held its inaugural meeting in February in a small town near

Moscow, attended by 193 delegates representing all 65 regions of the

Russian Federation. Wonyingly, three quarters of the delegates were army

officers. The rest included editors of various national-patriotic

papers, guests from Ukraine and Belarus and, interestingly,

representatives of the anti-globalist movement.

Also present were representatives of well known nationalist

organisations and parties such as the nazi Russian National Union (RNE),

the Russian Party, the Russian People's Party, the Officers' Union and

the Union of Pan-Slavic Journalists.

The three elected co-chairmen of the NDPR are all leaders of parties

that have joined together in this new bloc. Stanislav Terekhov, head of

the Officers' Union, is best known for his participation in the armed

attempt to oust the former president Boris Yeltsin in October 1993. He

was already considering creating a new structure at that time. Boris

Mironov, a former minister and leader of the Russian Patriotic Party,

and Alexander Sevastyanov, editor-in-chief of the newspaper

Natsionalnaya Gazeta,

are both notorious for making antisemitic statements like those on the

NDPR's website.

The NDPR's programme resembles that of the Officers' Union. Their ideal

for society reflects a nostalgia for Brezhnev's time intermingled with

some elements of pre-revolutionary Russia, such as the territorial

division of the country into clearly defined provinces. All elements of

society would be controlled by the state, which would own all land and

major factories. Independent small businesses would only be allowed in

the service sector.

The party has a strictly "no fun" policy for young people, who would be

corralled into sporting and

military-patriotic clubs. Western music and films would be banned. The

death penalty would be fully restored and abortion would be severely

restricted.

In foreign policy, the NDPR aims for reunification with Ukraine and

Belarus, now independent states, the strengthening of the army and an

aggressive policy of alliance with North Korea, China and Iraq, which

were all more or less allies of the former Soviet Union.

The NDPR's published programme for the wholesale reorganisation of life

in modem Russia amounts to 13 pages referring to the various social

strata of Russian society, including professional and state workers, the

technical intelligentsia, teachers, scientists and small business

people, but mainly to the army officers who founded the party. All these

groups have lost the relatively privileged social positions that they

occupied before Gorbachev's perestroika policy. Most of them have still

not found their place in the new Russia and feel lost and dissatisfied

with life. While such people are numerous, few are so politically active

as to be ready to participate in political organisations.

The leader of the People's National Party, Alexander

Ivanov-Sucharevsld, who also backs the NDPR, has great influence among

skinheads and is a wild antisemite. Although there are no directly

antisemitic statements or even insinuations in the NDPR's programme, if

one follows the statements of its leaders it quickly becomes clear that

Jews are the main enemy. The party emblem is the so-called kolovrat, a

stylised swastika used in various forms by many Russian

national-patriotic organisations.

The registration of the NDPR, with a membership of 11,000, provoked

furore in the media, with a major article in Izvestia and discussion on

the popular television programme Itogi and radio news broadcasts.

Questioned by journalists, the head of the Justice Ministry department

responsible claimed that the content of the NDPR documents presented for

registration was consistent with the Russian Constitution. A few days

later he rounded on the media saying, "Why didn't the mass media warn

the Justice Ministry, if journalists were so well informed about the

Searchlight November 2002 30

real activity of NDPR and even had audio and video material from its

foundation meeting?"

Eventually, a ministry official promised to check the documents and

activities of the NDPR again and promised that any criminal acts by the

party would be prosecuted. The NDPR is the first radical nationalist

party to be registered since the adoption of a new law under which only

registered political parties can fight elections.

One day after the NDPR's registration, the Justice Ministry gave the

go-ahead to yet another radical nationalist party with a brazenly

antisemitic platform, the People's Patriotic Party of Russia, headed by

the former Defence Minister Igor Rodionov. Vladimir Pribylovsky, an

analyst of nationalism at the Panorama political research centre,

believes that the authorities intend to make it easier to prosecute

nationalists by

getting them out in the open. The media fuss over the registration of

the NDPR is somewhat sudden, considering that die various fascist and

ultra-nationalist parties that have now come together have existed - and

been officially registered - since the beginning of the 1990s.

Anti-fascists are asking whether the latest development is a sign that

society is ready to admit the existence of fascism and extremism in

Russia and confess that the state structure is rotten with the same

sickness right up to the level of top ulterior and Justice Ministry

bureaucrats and the police.

Judging by a telephone interview with Viktor Korchagin, a senior NDPR

executive, by The Moscow Times, it appears that even the leaders

of the NDPR were surprised with the public sensation caused by the

party's registration.

From Mina Sodman in St Petersburg and Jean Raymond in Moscow

Ministry insists murder was not racist

CRITICISM OF THE RUSSIAN GOVERNMENT'S stance on racism has continued to

mount along with the level of racist violence. Although President

Vladimir Putin has made several declarations against racism, the reality

at grassroots level is rather different with little being done to

implement the tough action promised by the government.

"A sham is the best way to describe the government's policy of strongly

worded declarations." Lyudmila Alexeyeva, head of the Moscow Helsinki

Group, told The Moscow Times, adding that "a lot is done solely

to create a good image of Russia abroad. For example," she said, "when

skinheads beat up the son of a diplomat, we see a flurry of activity by

the authorities but when a common Azen falls victim, they don't care."

A major stumbling block of government policy has long been the almost

blind refusal of the authorities to recognise that certain crimes are

racist. In the majority of cases brought against skinheads, racism is

not acknowledged as a motive even when the victims are foreigners or

belong to ethnic minorities from the Caucasus.

On 10 September, a Senegalese student was attacked and savagely beaten

by a gang of seven youths in Moscow's Marxistskaya tube station. Three

days later a middle-aged Azen was killed in St Petersburg. Witnesses

reported that Magomed Magomedov was attacked by a 20 to 30-strong mob of

skinheads in the Pnmorsk district, near the stall from which he sold

watermelons to scratch out a meagre living. According to the police he

died from head injuries caused by a "metallic object". Witnesses added

that one of the attackers made a video of the entire incident.

Later in the evening, when the news of the killing started to

circulate, the press department of the Federal Ministry of Internal

Affairs (MVD) declared firmly, before even a preliminary investigation,

that Magomedov's murder had had a "private motive" and had absolutely

nothing to do with race hatred.

The MVD press officer also stated that a maximum of ten people took

part in "the street fight" and that stories about a video-recording and

the extremist background of the attackers represented "nothing but

destabilising rumour".

...

Searchlight November 2002 31

NETHERLANDS

From Jeroen Bosch of Alert! in Utrecht

Academic supports nazi 'Black Widow'

AN ACADEMIC at the University of Amsterdam has been suspended after he

wrote a letter of solidarity to a veteran nazi. Dr Boudewijn Heuts of

the Institute for Life Sciences contacted Florrie Rost van Tonningen in

September after a television broadcast, called Het Zwarte Schaap (the

Black Sheep), in which she was confronted by people critical of her

ideas and work.

His letter said: "Like you, I hope that at least a part of, for

example, the Northern European or the Australian race will be saved by

(so-called 'nazi' or 'racist') groups, who will make themselves strong

enough not to mix with other races".

Florrie Rost van Tonningen, 88, is the widow of Meinoud Rost van

Tonningen, a leading official of the National Socialist Movement (NSB)

in The Netherlands before and during the Second World War. Known as the

"Black Widow", Rost van Tonningen still advocates nazism and remains a

highly respected figure in international nazi circles, the more so

because she knew Hitler and Himmler personally.

Dr Heuts said he wanted to show her some light at the end of her life,

which has been so tough for her. "I had to do that according to my

conscience," he declared, "I wanted to take a stand against what has

been done to her."

His letter also complained that the television programme did not try to

understand "what they did to you by killing your husband". Officially,

Meinoud Rost van Tonningen died in a prison accident after the war, but

his widow claims that the Dutch government ordered his murder.

Rost van Tonningen's villa has since the early 1970s been a place of

nazi pilgrimage, where nazis of all ages gather for lectures and ancient

Teutonic rituals. At the start of the 1980s, she founded the Consortium

De Levensboom, which distributes nazi literature, organises meetings and

tries to promote the formation of a new fascist party in The

Netherlands. To this end she negotiated with the late Hans Janmaat of

the right-wing extremist Centrum Democraten and Wim Vreeswijk of the

Nederlands Blok, the now defunct sister party of the Vlaams Blok in

Belgium.

Rost van Tonningen is still a cult figure in Germany and lectures to

enthusiastic audiences of SS veterans and families. She often attends

the annual Yzerbedevaart (Iron Pilgrimage) in Diksmuide, Belgium, where

she is guaranteed a warm reception from her hard-core nazi fans.

At the beginning of the 1990s, Rost van Tonningen was convicted for

circulating racist and antisemitic literature and fined for insulting

the Jewish community. She was not deterred and continues to distribute

nazi hate books in English and German. '

Her much publicised plan to turn her villa into an exhibition centre

for nazi paraphernalia and study centre for "racial research" went awry,

when the local mayor denounced her. She then tried to buy a property

near Dortmund, Germany, formerly owned by Himmler, signing off her

abortive fundraising appeal with the SS motto Unsere Ehre heisst Treue.

She currently lives in a bungalow in Waasmunster.

Searchlight November 2002 28

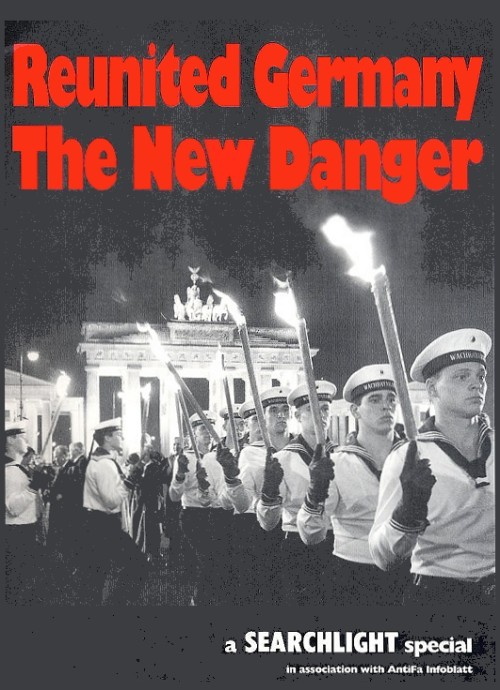

Mike Cohen

24 July 1935 - 2 October 2002

As we were preparing this edition of Searchlight, our

photographer, Mike Cohen, passed away. The photo on the front cover of

this month's magazine was the last one he took for us. Next month's

Searchlight will include tributes to Mike, accompanied by his photos.

Farewell dear comrade and friend, from all of us at Searchlight.

hagalil.com

31-10-02 |